2.14 - Analytical Process Thinking

Overview

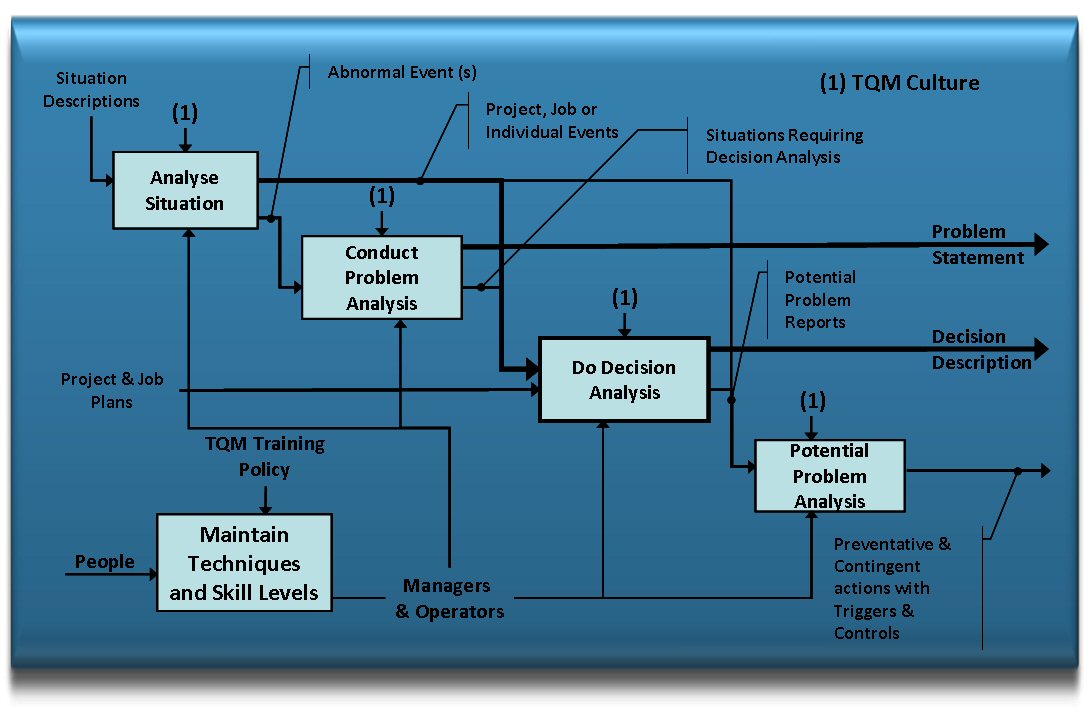

Tackling the day-to-day tasks of process improvement we need structured ways of thinking and approaching problems and to avoid risk and potential problems. Analytical Process Thinking allows us to apply structure to our problem solving processes. The structure is detailed below:-

- Situation Analysis (to specify the concern)

- Problem Analysis (to find the cause(s)) AND / OR

- Decision Analysis (to choose appropriate action) AND / OR

- Potential Problem Analysis (to plan implementation)

Analytical Thinking Process - Diagram

Situation Analysis

Situation Analysis is where the assigned tasks are identified such that we can determine how and in what order we handle them.

- Situation of concern – activities or tasks for which there is a need for some kind of action

- Separation – breaking down major concerns into specific sub-concerns that are easily identifiable as being tackled by one of the other thinking processes either in whole or in part.

- Priority Setting – setting priorities for dealing with the identified concerns with respect to the impact they will have on the company objectives or measures of performance. Priorities are set thus:-

- Seriousness – What’s the impact if we do nothing?

- Urgency – How much time needed before acting?

- Growth – How will things develop if action is delayed (better or Worse)

- What type of action needed – identifies what kind of thinking process will follow the situation analysis. Problem Analysis, Decision Analysis, Potential Problem Analysis or some combination.

Problem Analysis

Problem Analysis is where the probable cause of an abnormal or unexpected event has occurred. This ensures that all relevant factors are taken into account.

- Problem – A precise definition is required in the following terms:-

- A (DEVIATION) from what was planned or expected to happen (SHOULD) and what did happen (ACTUAL)

- The precise cause of the DEVIATION is unknown

- The cause needs to be found for effective action to be taken

- DEVIATION – a concise statement of the problem providing focus for more critical examination.

- Step by Step Approach – To avoid jumping to conclusions when the Deviation Statement is analysed a cautious step by step approach is needed to identify causes of causes. This may need to be iterated several times until a ‘cause unknown’ Deviation Statement is produced.

- Specification – This is a detailed statement of facts derived by rigorous systematic questioning. These are grouped into four areas to establish:-

- WHAT – To establish problem identity

- WHERE – To establish problem geography

- WHEN – To establish problem timing

- SCOPE – To establish problem extent or size

Decision Analysis

Decision Analysis is where we choose an action from several alternatives by making clear the judgement criteria on which the decision was based.

- Decision Statement – A short description of the purpose of the decision. It should not prejudice or constrain the choice. It merely provides a focus when looking for objectives.

- Objectives – These are the specific criteria against which our possible choices will be judged. Wherever possible they should be quantifiable. Some workers used check sheets for this. The objectives fall into two classes:-

- MUSTS – These are the objectives that are mandatory and must be fulfilled before any further consideration of an alternative (however good it is in other respects) can take place.

- WANTS – Those objectives which, once the MUSTS have been met we can use to compare the alternatives. Most likely a must will have specific values whereas a want is comparative. e.g.

- MUST – Not exceed £2000 capital cost

- WANT – Capital cost as low as possible

- Weighting Wants – Some wants will be more important to the decision than others. The relative importance is highlighted by giving a weighted score to each objective. Of course each weighting should be examined for possible bias.

- Alternatives – these are possible courses of action to achieve the purpose of the decision. Some will be obvious. Others might require approval and or expertise from someone else to execute.

- Evaluation of Alternatives – Against each objective for each alternative record and evaluate the data that may be available, or that which we may have to stop to get or that which needs to forecast.

- Evaluation of MUSTS – examine the critical data and determine whether the alternative is a yes or no. If NO there is point in considering that alternative further. If all alternatives are NO look for more alternatives by re-examination of the MUSTS or the original decision statement.

- Evaluation of WANTS – those alternatives that get through the MUSTS barrier are now compared relative each other via the WANTS.

- Scoring WANTS – consider each objective in turn and record the data available. When all data on the remaining YES or GO alternatives have been recorded certain alternatives will meet a specific WANT objective better than others. Score the alternative which meets the objective best with a 10 (even if you think it could be better met) and give the data on the other alternatives a score out of 10 using the data on the best as the basis for judgement.

- Tentative Decision – When the data on all alternatives have been compared and scored against each objective we are now in a position to take into account the original importance of the WANT objectives (weights). Multiply the score for each alternative by the objective weighting and add up the totals for each alternative. The TENTATIVE DECISION is that which has the highest weighted score as this takes into account both the relative merits of the data about the alternative and the degree of importance attached to each objective. There will be consequences of acting on this decision which could make it less attractive.

- Adverse Consequences – This is a list of those effects that might arise if we went ahead with a particular choice. The closer the overall weighted scores on the alternatives the more likely this step is likely to alter the decision. The adverse consequences are not a repeat of the data against the objectives that have already been evaluated. They are list of situations that could arise, if the decision is implemented, that will give cause for concern. Against the adverse consequences listed for any alternative we must now assess the risk involved.

- Risks – Risk consists of two main elements:-

- Probability – The likelihood that consequences will occur.

- Seriousness – The impact on our decision as it affects our operation if it does occur.

- We need now to score the adverse consequences out of 10 in terms each of Probability and seriousness. Thus 10/10 represents a certain disaster. Clearly it would be foolish to proceed with such an alternative unless we could put in place a plan of actions to greatly reduce the risk. Obviously it is the high risk which would steer us to our final choice.

- Best Decision – The best decision is that alternative which passes the MUSTS, fulfils the WANTS well, and has the least risk of ADVERSE CONSEQUENCES.

Note:

In making INTERIM, QUICK OR EMERGENCY DECISIONS, it is nearly always the short term consequences of our action and likely risks we are concerned with. We do not have the time to search for alternatives or consider more than one or two objectives. Thus the consideration of ADVERSE CONSEQUENCES is essential in this situation.

Particular consideration should be given to Murphy’s Law (10.04)

Potential Problem Analysis

Potential Problem Analysis is the process where we try to anticipate trouble and take action to minimise its likelihood or effects. Therefore Potential Problem Analysis implies less Problem Analysis and costs far less (see Change Management

2.04, and Failure Modes Effects Analysis (FMEA) 5.30). Potential Problem Analysis can be applied to a Plan or Project or a specific event. If a specific event needs protecting then we need specific Potential Problems to be analysed.

- Plan Statement – A short description of the plan on which the potential problem analysis is to be performed to provide a boundary and scope.

- Plan Stages – A list of the stages, phases and work packets with times scales and responsibilities identified.

- Critical Areas – Identify those elements of the plan most likely to cause problems together with a priority indication to determine what to attack first. Critical areas indicate where, initially, to look for potential trouble. For each critical element in turn identify:

- Specific Potential Problems – Those specific things which could go wrong together with an assessment of their risk (Probability / Seriousness). If, for instance a Decision Analysis was performed first we will be looking at objectives that were poorly met and their adverse consequences, which we have not yet seen how to overcome. This will help identify the Specific Potential Problems. It would be good to get a fresh pair of eyes and ask what could go wrong at a particular stage and use the question implied by the following headings to elicit solutions. For each specific problem where the risk justifies the action, identify:-

- Likely Causes – There will always be a cause for something going wrong. Here we try to guess those events which will trigger those causes. It is clear we have to identify Specific Potential Problems for which we have a valid cause.

- Priority – Attach a priority to each likely cause that reflects its probability of occurrence. This provides an indication of how much preventative action should be taken.

- Preventative Action – Against each likely cause it is possible to identify some, often, very simple means which will reduce its probability of occurrence. List the actions or the acceptance of the risk identified. These actions should always be implemented before the time on which that element of the plan becomes operational.

- For each Specific Potential Problem where the risk justifies action:

- Contingent Action – Despite all the preventative action taken it will be occasionally be found that on the day that the stage in our plan becomes operational that the Specific Problems which were identified DO occur. Then the contingent actions that were prepared can be deployed. Contingent actions seek to minimise the effects of something going wrong.

- Triggers and Control – For both preventive and contingent actions we need to identify what will be needed (TRIGGERS) to set the actions into motion. So we need to monitor the execution of the plan and use CONTROLS to bring it back on course. Identify these aspects and link them to each preventative or contingent action that has been recorded. This also provides terms of reference (TOR) for briefing the person responsible for the action.

Notes:

Occasionally it will only be possible to take either preventative or contingent action but not both. In either case, since the options of action are now greatly restricted, there is a need to be much more thorough in the analysis.