6.14 - When to Change a Part Number

In this guide, the word “part” is used, in its most general sense to mean any item, product, sub-assembly, component or raw material.

The Problem

For identification and control purposes, any part that is ever stocked, shipped and /or scheduled needs to have a unique part number. When making modifications to a part specification, engineers often do not know whether or not to assign a new part number. Opinions differ not only in engineering but also in other departments of the company. The problem is compounded in some companies where the part number is used for two separate functions:

- a) to identify the parts and

- b) to identify the drawings of the parts

Discussion

Since 1812, when rifles were first assembled from standardised parts, everyone has become increasingly familiar with the ability to repair a product by replacing the faulty component with a component taken from a similar product. Part standardisation was an important step in the progress of manufacturing. This familiarity has led to the popular belief that the replaced and the replacement components are identical. This misunderstanding is not at all helpful when trying to solve the problem of if or when to change a part number. For example:

“One part number must not identify two or more items that differ from each other, if ever so slightly”

Statements such as this show a fundamental lack of appreciation of the design process. When designing a part, a good engineer will allow manufacturing as much flexibility as possible to produce a satisfactory part at minimum cost. The specification will normally take the form of limits, within which manufacturing must operate, outside of which the engineer:

- a) is confident that the part will cease to physically interchangeable or

- b) estimates that the performance of the part will be inadequate

The specification limits needed to satisfy (b) are normally “tighter” than those needed to satisfy (a) e.g. two springs of similar outside diameter and length are physically interchangeable but, if the wire diameter or material is different, only one may give the desired performance. Just as no two people identical, no two parts ever made are identical. There are always slight differences, within limits.

Other suggestions for solving the problem also put emphasis on the differences between parts:

“If the form, fit or function of a part is changed, it must have a new identifier a new part number”.

It is implied that differences in form, fit or function are distinct. In fact they tend not to be. Once the engineer has decided what type of change the modification in question is, he is still left wondering whether the change of form, or fit, or function is significant enough to justify allocating a new part number. For example, a 10% increase to the clearance between a shaft and a bearing is a change of “fit”, but would not normally justify a new part number.

A Solution

It is proposed that the key to solving the problem is to analyse the similarities between parts, not the differences. Two parts identified by the same part number must be sufficiently similar to:

- a) be physically interchangeable in the product AND

- b) both give adequate performance in all present and foreseeable applications.

The important point is that the performance of both the parts is adequate; they will never be the same. There will always be differences. In a nutshell they should only have the same part number if they can be mixed in the stores (i.e. in the same stock bin).

What is Physical Inter-changeability?

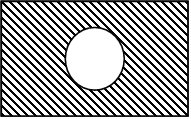

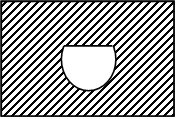

It is important that both the replaced and replacement parts are interchangeable in all applications, if they are to be identified by the same part number. A part that replaces another for only some, or can be used in more applications should not be considered as interchangeable. The two parts must be identified by different part numbers. Physical inter-changeability is wholly determined by the specified dimensions.

What is adequate Performance?

Adequate performance can be measured (or at least an opinion established) by either direct or indirect tests:-

1) Direct Tests: |

a) ease or efficiency of operation of part in service or on endurance test rig.

b) life of part in service, or on endurance test rig. |

2) Indirect Tests: |

a) Tensile Strength of part

b) Material Quality of part

c) other standard tests e.g. as specified by various standards bodies |

Any of the tests can be carried out by the company, by any customer or any other body (usually at the company’s or customers’ request). Given the number of permutations of test and testers there obviously will be a wide range of opinion regarding what performance is adequate for a particular part.

This is the reason that traditional (rigid) decision rules for changing part numbers do not work. It must be acknowledged that in extreme cases, it is sometimes necessary to change a part because a particular customer firmly holds an unjustified opinion of the performance of that part. If this is done, it will be necessary to schedule the new part for that customer and it is therefore essential that the part number is also changed.

Examples of Engineering Changes and Part Number Decisions

|

Replaced & Replacement Parts |

Type of Change |

Physically Interchangeable |

Company Opinion: Both OK |

Customer Opinion: Both OK |

Same Part No |

1) Inconsequential drawing error corrected |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

2) Part original limits tighter than necessary to give adequate performance, therefore relaxed |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

3) Part performance adequate but part changed to reduce cost of manufacture |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

4) Part performance considered adequate by company, but it is expected that at least one customer will not agree. (i.e. Decision to change because of risk of complaint) |

Yes |

Yes |

??? |

NO |

5) Opinion differs within company regarding performance change required, but eventually decision is made to change part. |

Yes |

??? |

Yes |

No |

6) As consequence of customer complaint, it is agreed to change the part. |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

7) If anybody considers part performance inadequate in any test and change is authorised |

Case 1 |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Case 2 |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Case 3 |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

8) Part NOT physically interchangeable in all present and foreseeable applications |

No |

Yes or NO |

Yes or

No |

No |

Examples 4, 5 and 6 deliberately highlight some awkward situations where the engineer needs advice. In such circumstances, it is the reason for the change – not the technicalities of the change – that determines whether or not to assign a new part number. It is the responsibility of the Engineering Change co-ordinator to advise the engineer on this.

If it is decided to assign a new number to a part, it must then be decided whether or not to assign a new number to its parent. The criteria for deciding this are exactly the same, at all levels in the Bill of Material structure.

Any change to the specification of a part has to be recorded on the drawing and therefore the drawing number should be changed. This is normally achieved by adding a revision letter to the drawing identification. However if:

- a) the change relates to inter-changeability or performance (as described above) and

- b) the part number and drawing number are the same

then it is necessary to change the whole number on the drawing. Any temptation not to change the part number as prescribed, because of the inconvenience of changing the number on the drawing, must be resisted.

Handling Part and Drawing Number Changes

In manual systems each change is handled on a case by case basis, as described above (the information in this paper is from a company procedure from the 1950’s and 60’s), with a number of work-arounds, being employed as expedience demands. (Nothing new under the sun!)

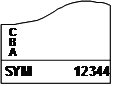

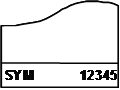

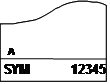

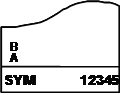

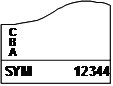

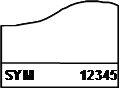

The next table is presented to indicate some of the part numbering, issue, revision and document controls that must be formalised (or NOT) when implementing computerised PLM systems.

All Applications |

|

|

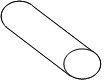

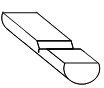

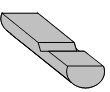

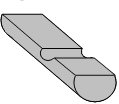

Development of a Peg |

|

|

|

|

Eng Change Reason |

|

Standardize on one peg |

Achieve adequate performance |

Reduce M/C tool set up time |

|

Adequate performance? |

Yes |

NO |

Yes |

Yes |

Drawing(s) |

|

|

|

|

Part Number

Systems |

W |

12344 |

12345 |

12345 |

12345 |

X |

12344-003 |

12345-000 |

12345-001 |

12345-002 |

Y |

12344-003 |

12345-000 |

12346-000 |

12346-001 |

Z |

122441 |

12345 |

12346 |

12346 |

Drawing Number System |

Same as part No |

|

|

|

|

Differs from part No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

With computerised Product Life-cycle Management (PLM) change management must be formally controlled, but not to tightly, or some of the reasons for implementing PLM will not be achieved. Of particular concern, are document control, configuration management, traceability and product liability issues. Without proper attention the PLM installation benefits will fall far short of the desired results.